Opinion

Gauhati Cine Club’s 60th Anniversary: Unmet Expectations

If Gauhati cine club wants to honour its legacy, it needs to start listening again, not just to old names and habits, but to new voices, new curators, new participants.

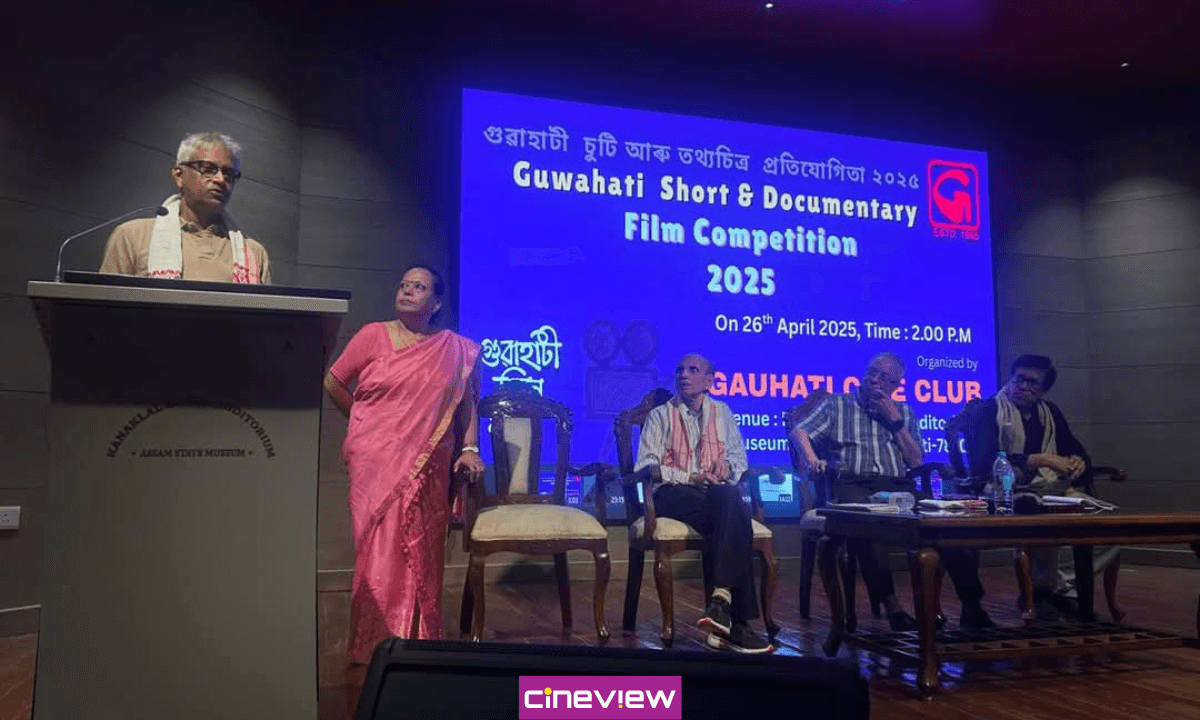

It is almost evening, around 5 p.m. We have finished watching seven films at the Kanak Lal Baruah Auditorium, at an event organized by the Gauhati Cine Club. Not that you would guess anything was happening if you looked from the outside of the Assam State Museum, there were no posters, no hoardings, nothing at all. Even when I entered, I had no idea where exactly the film screening was happening.

At the tea break after watching the films, I couldn’t help but wonder: if the club has been around for 60 long years, how is it that the standard of the event still feels stuck somewhere far behind, especially when newer organizations have managed to do better in much less time? Is it because we genuinely lack resources? Or is it just the casualness with which we treat film as merely a leisure activity that doesn’t require as much thought as political or social gatherings? Or does the exclusiveness of the club also play a role in the mediocrity of the festival?

Let’s try to understand what went wrong in the organization of the event and how it could have been made more engaging.

It was in 1965 when Dr. Bhupen Hazarika, to promote the reach of cinema among the people of Assam, established the Gauhati Cine Club. Over the years, they have organized many events in and around Guwahati, published notable works on cinema, and are known to have given voice to many filmmakers, film critics, and film enthusiasts.

On 26th April 2025, it was the club’s 60th anniversary, which I had expected to be an insightful event for someone like me, a new enthusiast of film. But the whole event, and the way it was approached, didn’t seem professional; it felt more like a personal gathering where a few random films were selected and screened without much regard for the craft of filmmaking.

Of the 7 films that were screened at the festival, except for Chanchisoa by Elvachisa Ch Sangma and Dipankar Das, and Himjyoti Talukdar’s Ilish, the rest were below average, hardly anything worth remembering. The Best Film award went to Character, a painfully mediocre story about a man struggling in the city while his daughter at home complains because he never visits. The writing and execution were so weak that the dialogues often felt forced and awkward, and made the entire scenes fall flat.

Then there’s Ducklings of Nakatha, which somehow won Best Screenplay. It’s about a man who applies for a loan and gets scammed by online fraudsters. Not only does the film fail to make you believe its story, but some scenes, like that random dream sequence, just leave you wondering what exactly the film was trying to do. By the time it ends, you realise the plot never held together in the first place. When these two films got awards, I genuinely started questioning the sincerity of the festival and whether they actually care about good cinema.

Ilish and Chanchisoa also won Best Director and Best Cinematographer, respectively, and those were the only awards that felt deserved. In fact, they deserved more. But the way the awards were spread out across all the films made it look like the festival just wanted to please everyone, turning the whole thing into a formality rather than genuine recognition.

Other films were simply tone-deaf. In today’s era, where many new filmmakers with real potential are emerging, these films feel outdated. It was disappointing to see that these were selected for screening, while others, submitted by budding filmmakers doing commendable work, were left out. Their posters were only shown in a slideshow before the screening of the selected films. Some of them seemed promising, which made me wonder: why weren’t they chosen? This question stayed with me even after watching all the films.

Not just the standards of the film, the entire event lacked coordination among the organizers. It felt like they were so full of themselves that they hardly cared about the basic decorum one usually expects at a film festival. This made me think about the casualness of the whole event. Does it come from the organizers’ complete lack of ambition, or are they simply unaware of how film festivals are run these days? Or maybe they are just not in touch with other clubs that are organizing far better festivals, in Assam or beyond.

Film festivals are integral to the development of the craft of cinema in any region, and they significantly contribute to shaping cinematic discourse for filmmakers, film students, film critics, and even casual cinema viewers. If we look at the history of film festivals, we find many examples where this has been the case. Take, for instance, François Truffaut’s essay “A Certain Tendency in the French Cinema,” which called for a break from the stale conventions of French cinema. Though he was later banned from the Cannes Film Festival, his debut film The 400 Blows won an award at Cannes in 1959, an event that helped trigger the French New Wave and changed the course of filmmaking in France.

Similarly, filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Steven Soderbergh, and Ava DuVernay emerged from the Sundance Film Festival, which played a critical role in shaping American independent cinema. In India, Satyajit Ray found his first inspiration in the neorealist films shown at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in 1952, and applied those influences in his debut Pather Panchali.

IFFI not only showcased films from Japan, France, and Iran, but also introduced regional auteurs like Adoor Gopalakrishnan to both domestic and international audiences. It became more than just a screening platform, it evolved into a space where filmmakers could meet and learn from each other. Famously, Ritwik Ghatak met Vsevolod Pudovkin at IFFI, and the influence of Soviet constructivist cinema is clearly visible in Ghatak’s work. In films like Meghe Dhaka Tara and Subarnarekha, Ghatak uses montage not just to tell a story but to evoke deep psychological and emotional states, something that shows Pudovkin’s influence over him

Thus, film festivals have acted as a catalyst that created, ignited, and nurtured filmmakers, critics, and film buffs for generations across different regions. But here, it is important to understand what made those film festivals landmark events, what made them more noteworthy than events like the one organized by the Gauhati Cine Club?

If we only take the example of a few successful Indian film festivals established much later than the Gauhati Cine Club itself like the Kolkata International Film Festival (established in 1995), the Chennai International Film Festival (started in 2003), or even relatively newer ones like the Habitat International Film Festival in Delhi, we find a common factor: they were all curated and managed by individuals or institutions with a background in film studies, criticism, or cultural programming.

For instance, the Kolkata International Film Festival is organized by the West Bengal Film Centre under the state government, and its curatorial board has included noted filmmakers, academics, and critics. The Chennai festival is backed by the Indo Cine Appreciation Foundation, run by cinephiles and scholars who have actively collaborated with global film bodies. Habitat’s festival, organized by the India Habitat Centre, consistently involves curators who have worked with international film circuits and have academic or practical experience in film curation. Their backgrounds not only ensure thoughtful selection and programming of the films, but also access to international networks, technical know-how, and sensitivity to cinematic discourse that make their events more vibrant, relevant, and influential.

But then the question arises: do we not have trained people in Guwahati or Assam who can curate effective film festivals? We certainly do. Even in the Gauhati Cine Club, there are people who have done extensive work on cinema. But what is lacking is the second point that makes a film festival effective or successful: the active participation of film students and young minds as volunteers and organizers.

Bringing in young minds as volunteers injects new energy into an event. Not only does their participation shape film festivals for the better, but these festivals are also supposed to give them significant exposure to films, to filmmakers, and to the practicalities of filmmaking, which will motivate them to work on the craft themselves. But are the Gauhati Cine Club giving that exposure to the young minds?

A film festival is not only about the films but also about what happens beyond the screenings, about the crowd, the conversations people have during the tea breaks, and everything in between. At the event organized by the Gauhati Cine Club, I couldn’t help but notice how exclusive those tea-break conversations were. The elders were just busy among themselves and didn’t make an effort to include new people in their discussions, which made the festival feel somewhat incomplete.

Older clubs often fall into the trap of institutional inertia or resistance to change within; even if young people get engaged, they are given very little to no room to participate in decision-making, and the elders cling to their comfort zones with outdated methods.

If the club truly wants to honour its legacy, it needs to start listening again, not just to old names and habits, but to new voices, new curators, new participants. Starting next time, let the films of young, promising filmmakers be screened, not just their posters shown in a passing slideshow. A film festival is about how we gather around films, how we create space for exchange, for challenge, and for possibility. If that doesn’t happen, then even an event held in the name of cinema ends up missing what cinema really offers us.

Opinion9 months ago

Opinion9 months agoMorality, Obscenity and “Mou Bihu”

Film Reviews1 year ago

Film Reviews1 year agoJoy Hanu Man: The Hero Amongst Us

Film Reviews1 year ago

Film Reviews1 year agoSundarpur Chaos or Chaos in Director’s Vision

Film Reviews1 year ago

Film Reviews1 year agoFor Assamese cinema to flourish, movies like Sikaar are necessary

Film Reviews1 year ago

Film Reviews1 year agoLocal Kung Fu 3: Is Assamese Comedy Evolving?

Film Reviews2 years ago

Film Reviews2 years agoBidurbhai’s Shocking Caricature of Queers: Painful but Not Surprising

Film Reviews2 years ago

Film Reviews2 years agoBasumatary’s Jiya is a Beacon of Hope for Assamese Cinema

Film Reviews1 year ago

Film Reviews1 year agoAbhimanyu: Questioning the system, one frame at a time